- Sri Lanka recently conducted a three-day elephant survey by counting the animals as they visited watering holes across the country.

- This is the first survey of its kind to be conducted since 2011, when the minimum number of elephants in Sri Lanka was estimated at 5,879.

- In the interim period, a total of 4,262 elephants have died, most of them in conflict with humans, so it will not be clear until the results are published in a month whether the population trend is up or down.

- Despite possible errors in the overall count, the survey is expected to provide important insights, such as the male-to-female ratio and the number of calves, which are important indicators of the health of Sri Lanka’s Asian elephant population.

COLOMBO – This past August 17 would have been just another ordinary day for Sri Lanka’s elephants: feeding, drinking, resting and, for some, raiding nearby farms. But for Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) staff and thousands of volunteers, it was the start of a busy weekend as they carried out the country’s elephant count – the first such count in 13 years.

With food rations for three days, some volunteers in remote areas planted temporary trees overlooking watering holes, while others found safe places where they still had a good view of Asian elephants (The biggest elephant) Each participant was given a sheet to fill in. DWC used a technique known as “watering hole counts,” which provides a rough estimate of elephant abundance from the number of elephants seen visiting watering holes.

“The month of August was chosen for the count as it is the driest month in Sri Lanka, so elephants in need of water visit these sources to quench their thirst,” said Chandana Sooriyabandara, director general of DWC. The department identified 3,130 such water sources frequented by elephants and deployed nearly 8,000 people to conduct a three-day census starting August 17, Sooriyabandara told Mongabay. The last day of the count, August 19, coincided with a full moon, allowing the desert to be illuminated by moonlight and making it easier to count the elephants.

Did the rain interfere with the calculation?

However, the months of preparation were threatened by the unseasonal rains that Sri Lanka began to receive a few weeks before the start of counting. The rain created pools of water, allowing the elephants to drink without having to visit monitored watering holes. A similar count planned for 2019 had to be canceled due to rain, and there were calls to postpone this year’s count as well, given that the results of the survey would be used for elephant conservation in the next decade.

Despite these concerns, and heavy rain in several areas, the DWC considered the count a success. It is now analyzing the data, and says it will take at least a month to release the results of the investigation.

Beyond the total numbers, understanding the overall structure and composition of elephant populations is important, said Shanmugasundaram Wijeyamohan of Vavuniya University. The water hole counting method was introduced in Sri Lanka by the late Charles Santiapillai, a renowned elephant conservationist and biologist, in 1992, and the last complete elephant count, in 2011, also used this method.

Controversy and criticism

The method of counting watering holes has its share of critics, with some arguing that not all elephants may visit monitored watering holes, as some may prefer rivers or other water sources. Different methods of examining elephants each have their own flaws, Wijeyamohan. Aerial tracking is used in many parts of Africa where savanna elephants (Loxodonta africana) various in open areas, but in the forests of Sri Lanka this method will not be possible, he said. Another method, dung count, involves counting elephant dung along pre-defined paths to estimate population, but does not provide demographic data or insight into elephant population structure.

A 2011 census estimated that Sri Lanka was home to 5,879 elephants, with the largest numbers in the North Central, Eastern and Northern provinces, which are important habitats for the species. The census also provided insight into the demographics of the population, including a male to female ratio of 1:3.

According to calculations, 55% of the population were adult elephants, and 1,107 calves. These results, especially the sex ratio and the number of calves, showed a healthy elephant population, Wijeyamohan told Mongabay. “We need to examine the results of the 2024 survey to assess any significant changes in this ratio rather than focusing solely on the number of elephants,” he added.

The main threat to Sri Lankan elephants is conflict with humans. Since the 2011 census, 4,000 elephants have died – almost the entire number counted in the last survey.

Unbelievable calculations

“Calculating the total number of elephants in a country or region is not easy, and the method of counting water holes will not give an accurate total,” said Prithiviraj Fernando, an elephant biologist who heads the Center for Conservation and Research (CCRSL) and has done. pioneering research on Asian elephants.

“The big issue with waterhole surveys is that the number of elephants counted is directly proportional to the number of survey points. If the same number of points as last time are used, the same number will be counted; fewer points would result in a lower count, and more points would lead to higher numbers,” Fernando told Mongabay.

Counting elephants is difficult, and there is no easy or completely reliable method, he added. Methods such as identifying individual elephants through photographs or tag recapture, which involves tagging elephants and releasing them, can provide reliable estimates but are time-consuming, expensive, and impractical at the country level, Fernando said.

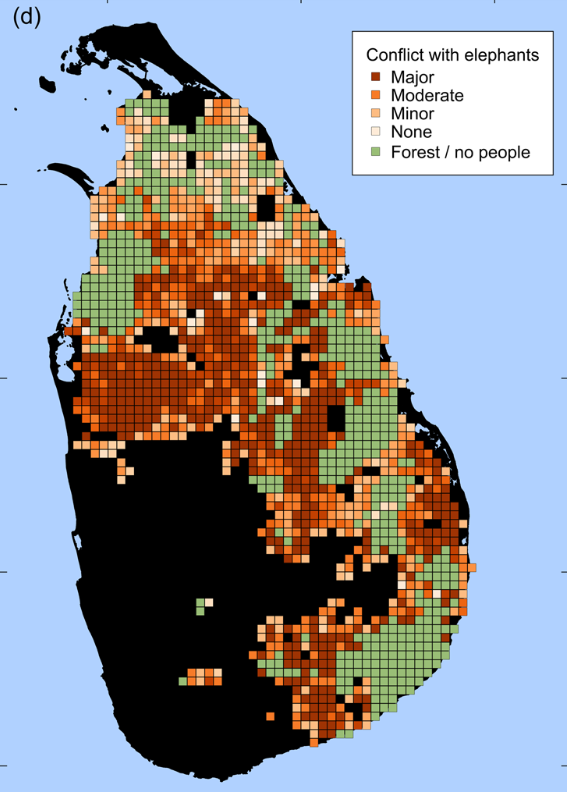

More useful research, he added, would assess where elephants are found, whether they comprise herds or only males, and whether they are seasonal or resident. His own survey, carried out by dividing the country into 25 square kilometer (10 square mile) blocks, found wild elephants in 60% of Sri Lanka, and 70% of that range is shared by the population, leading to serious conflicts between of humans. and elephants. Even without accurate numbers, this information is important for conservation efforts, Fernando told Mongabay.

He suggested such studies, according to the questionnaire, could be carried out more effectively in areas of conservation concern, such as at the edges of elephant distribution or where development projects are being planned. Such data can then inform conservation and management decisions.

A hidden agenda?

Sri Lankan environmentalists have raised concerns that the results of the latest census may be misused. In 2011, they questioned why the inventory also recorded the types of elephant tusks observed, saying this had no conservation value but could be useful to people who want to capture wild elephants. Sri Lanka has a tradition of flying elephants in religious processions, and owning an elephant, and especially a tusker, is considered a status symbol, leading to the illegal capture of elephants from the wild in the past. Activists have repeatedly expressed concern about the true purpose behind collecting such data.

This time, such fears have been given weight by a call from Jagath Priyankara, a member of parliament, to address the human-elephant conflict by reducing the wild elephant population. Priyankara has proposed measures such as exporting elephants to foreign countries, and capturing and training them for slavery. Environmentalists say that if the 2024 census reveals a higher number of elephants than in 2011, local politicians may put pressure on the government to capture and remove elephants from certain areas. High numbers can also suggest there are too many elephants, leading to reduced conservation efforts. But higher numbers should not be used to justify killing elephants or capturing them for domestication, environmentalists say.

Poster image: Mkinga and herd of elephants in Sri Lanka. Photo by Mevan Piyaseana.

One elephant a day: Sri Lanka’s wildlife crisis escalates as death toll rises

Quote:

Fernando, P., De Silva, MK, Jayasinghe, LK, Janaka, HK, & Pastorini, J. (2019). The first nationwide survey of the endangered Asian elephant: Towards better conservation and management in Sri Lanka. Oryx, 55(1), 46-55. doi:10.1017/S0030605318001254

#Sri #Lanka #completing #elephant #census #uncertainty